Troubleshoot network connection with traffic mirroring

Sometimes you have to look at the network packets to really understand what is going on. This is exactly what happened during a project involving misconfigured network setup from on-premise to AWS VPC. I’ll walk you through my experience of how AWS traffic mirroring helped me get to the root cause.

Background

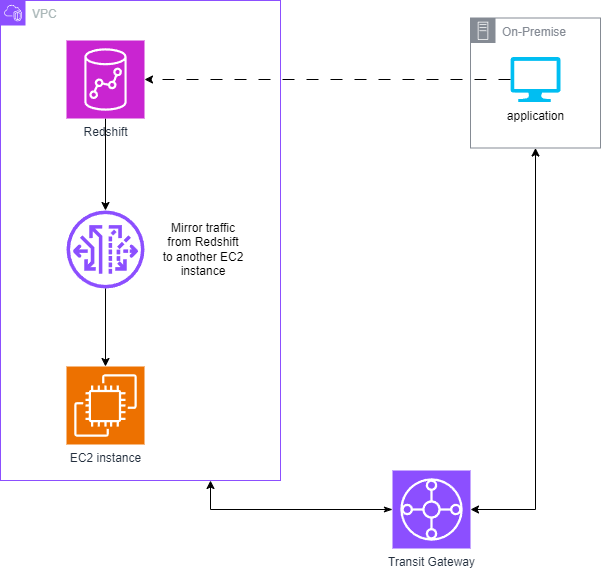

The client had chosen AWS Redshift as their data warehousing solution, hosting it within an AWS VPC. To seamlessly integrate it with their on-premise network, they leveraged AWS Transit Gateway for secure and efficient connectivity.

Their custom application, operating within their on-premise network, establishes connections directly with Redshift for seamless data interaction. This application is running Python and connects to the Redshift cluster using Psycopg2 library.

Everything was smooth sailing for weeks until they underwent a switch and router replacement in their network. Suddenly, the application hit a snag and couldn’t connect to the Redshift cluster—or so we initially believed.

The investigation begins

The investigation began with a deep dive into the Python code itself, searching for any potential issues. Despite its apparent simplicity, this crucial snippet responsible for connecting to the Redshift cluster consistently timed out:

def connect():

secret_arn = ssm.get_parameter(

Name="/redshift_secret_arn", WithDecryption=True

)["Parameter"]["Value"]

secret_dict = get_secret_dict(secret_arn)

db_host = secret_dict["host"]

db_port = secret_dict["port"]

db_name = secret_dict["dbname"]

db_user = secret_dict["username"]

db_password = secret_dict["password"]

con = psycopg2.connect(

dbname=db_name, host=db_host, port=db_port, user=db_user, password=db_password

)

con.autocommit = True

Since there were no recent changes to the application code, we ruled out the application itself as the culprit. To further diagnose the issue, we attempted to create a new Redshift cluster and connect to it instead. Surprisingly, we encountered the same connection timeout, deepening the mystery.

With no clear solution in sight, it was time to get my hands dirty and delve into the world of network packets.

What’s inside the packets

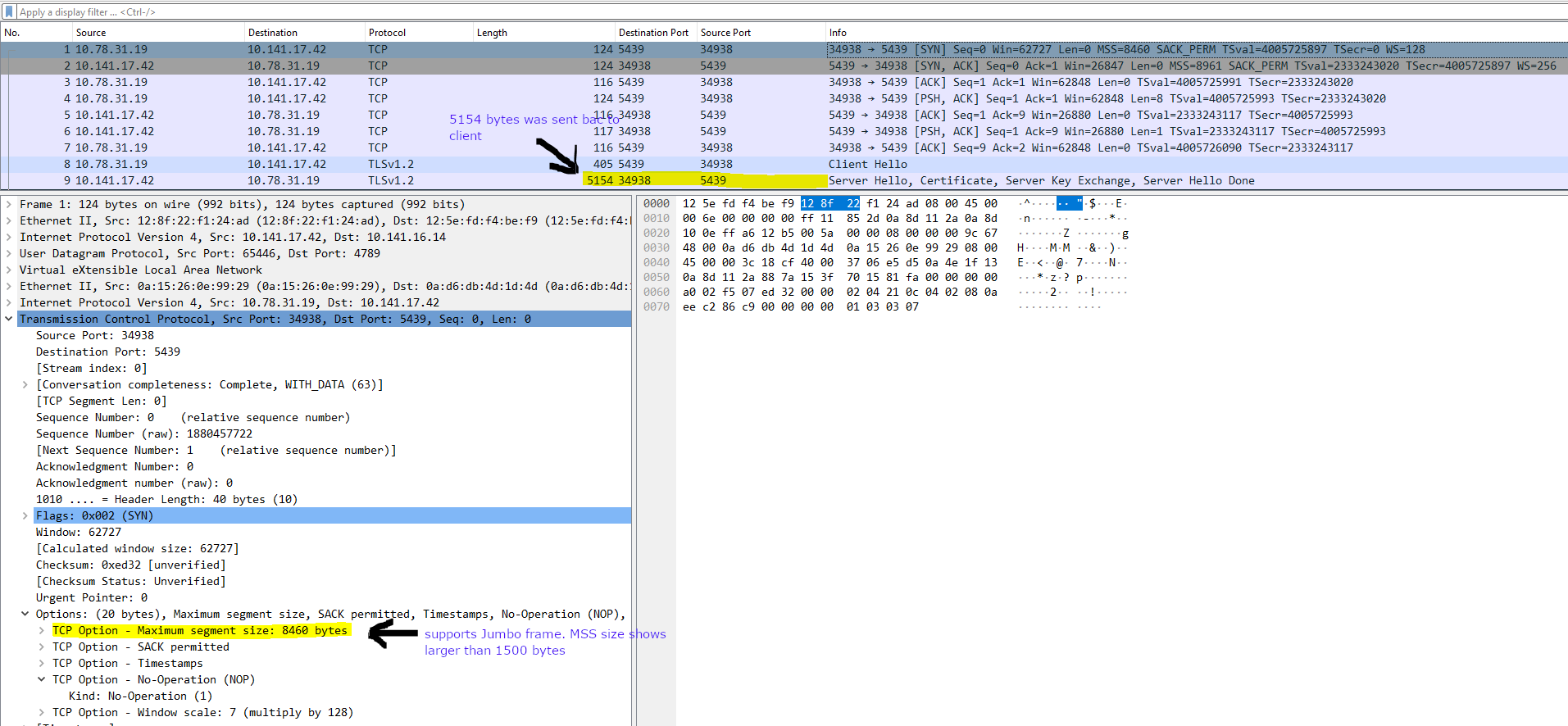

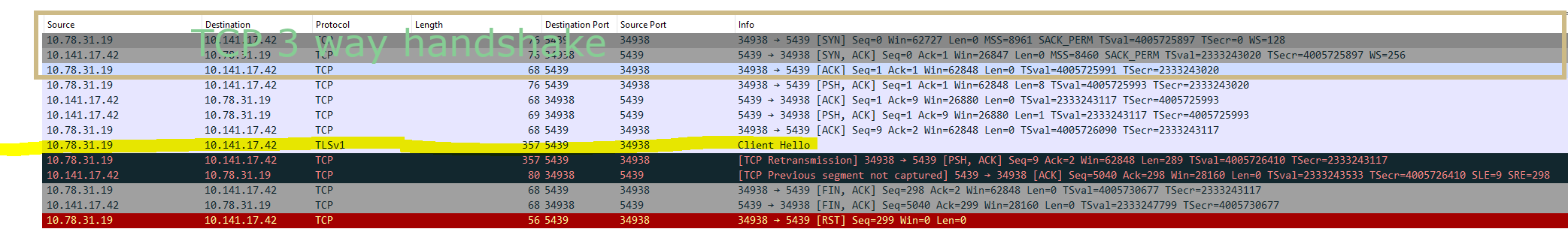

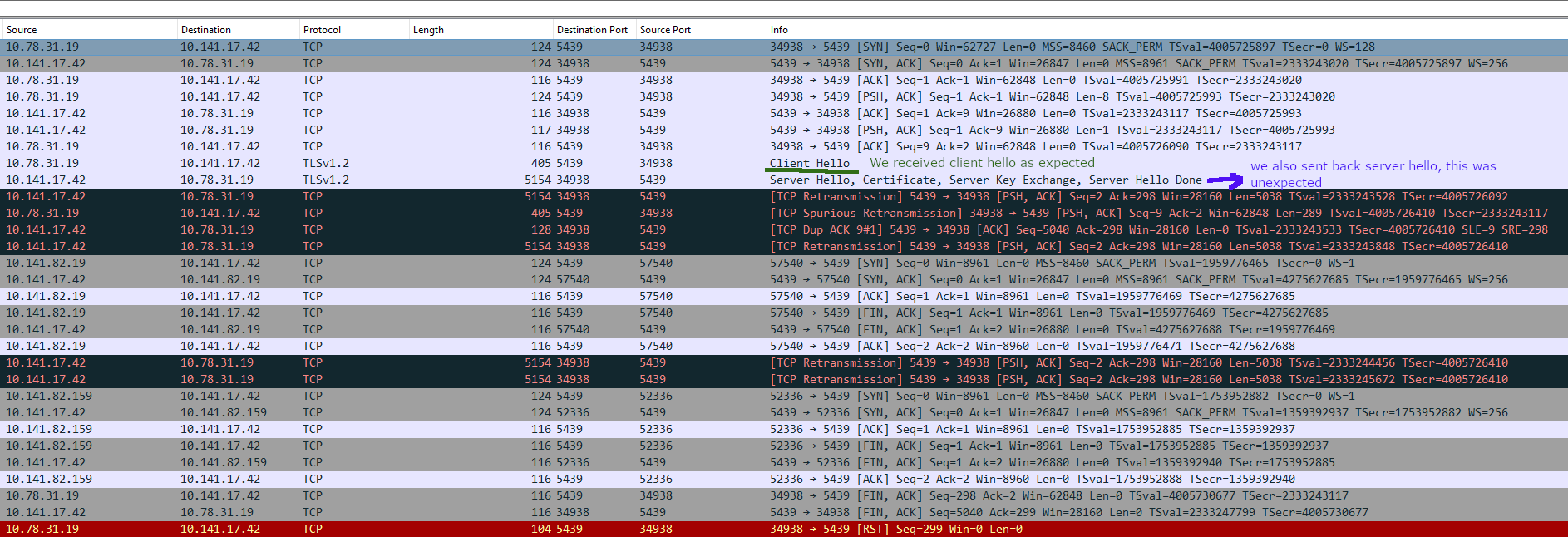

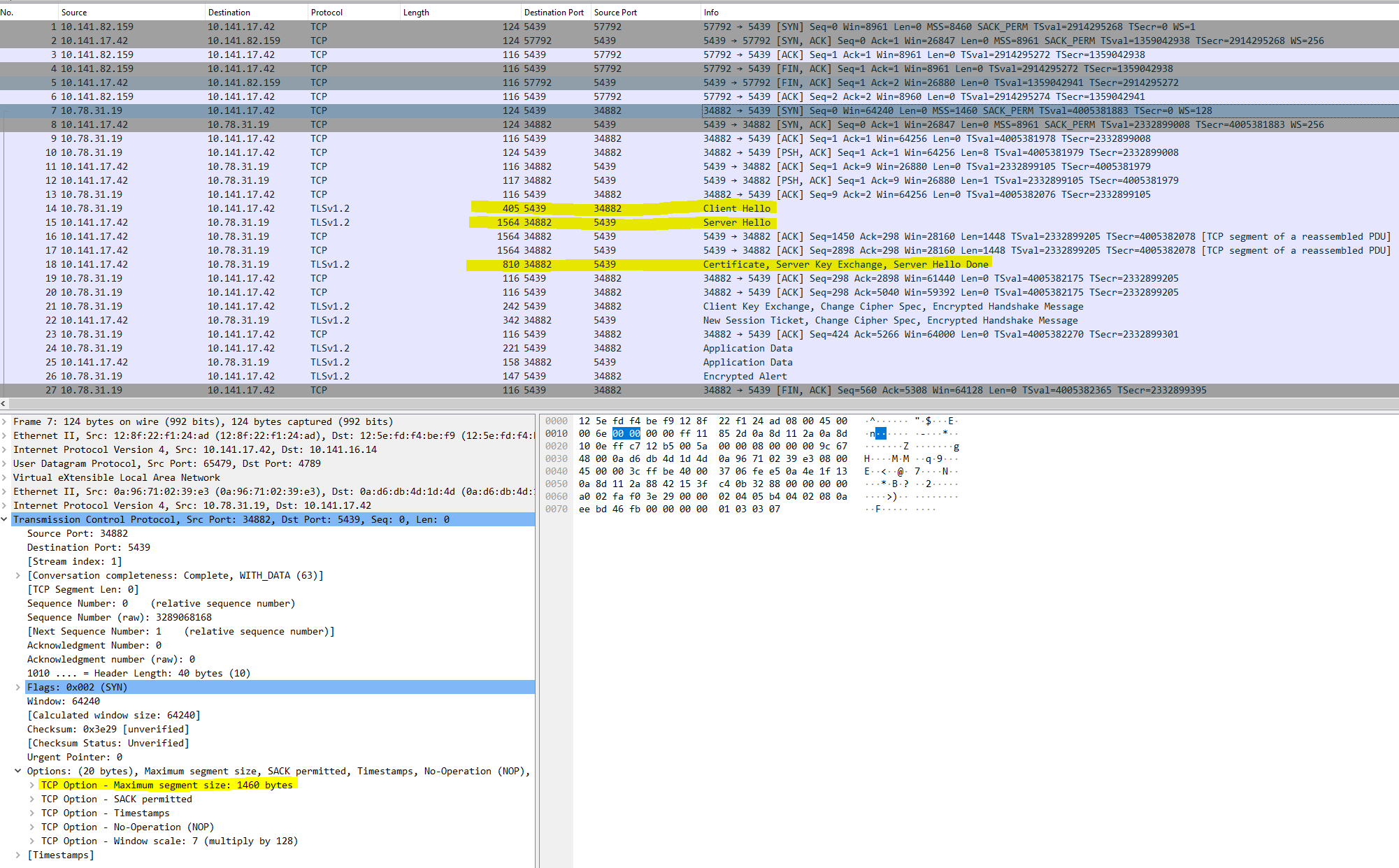

Equipped with Wireshark installed on the application server, I commenced capturing and analyzing the network traffic traversing in and out of the application. The enclosed packet capture substantiates our suspicion that the application encountered connectivity issues with the Redshift cluster. The packet capture indicates a discrepancy during the TLS handshake, wherein the client sent a client hello message but did not receive a server hello response from the server.

Here is a quick refresh on TLS handshaking, see figure 3:

The primary goal of TLS is to provide a secure channel between two communicating peers. And the steps involved can be explained briefly as follows:

The ‘client hello’ message: The client sends a hello message to the server.

The ‘server hello’ message: The server reply with a server hello, certificate and server hello done message back to the client together with server’s SSL certificate.

Client key exchange message: During this stage the client exchanges key secrets with the server

Session keys created: Both client and server generates session keys that can then be used for secure communication

So, based on the packet capture in figure 2, it appears that the issue does not stem from server unreachability. The TCP three-way handshake was successfully established. However, the problem lies within the TLS handshake process.

The only definitive method is to capture the server-side traffic. AWS Traffic mirroring precisely fulfills this requirement.

AWS Traffic Mirroring

If you’re not acquainted with AWS Traffic Mirroring, it’s a feature within AWS VPC enabling the replication of network traffic from one elastic network interface to another, including network load balancers or Gateway Load Balancer endpoints.

To analyze the traffic, we’ve set up an EC2 Linux instance designated as the mirroring target. This instance will execute TCP dump to capture the mirrored traffic, saving it to a file for further analysis using Wireshark.

tcpdump -i eth0 port not 22 -w packets.pcap

The above command was executed to start capturing live streams of network packets (excluding port 22) and dump it to the file packets.pcap.

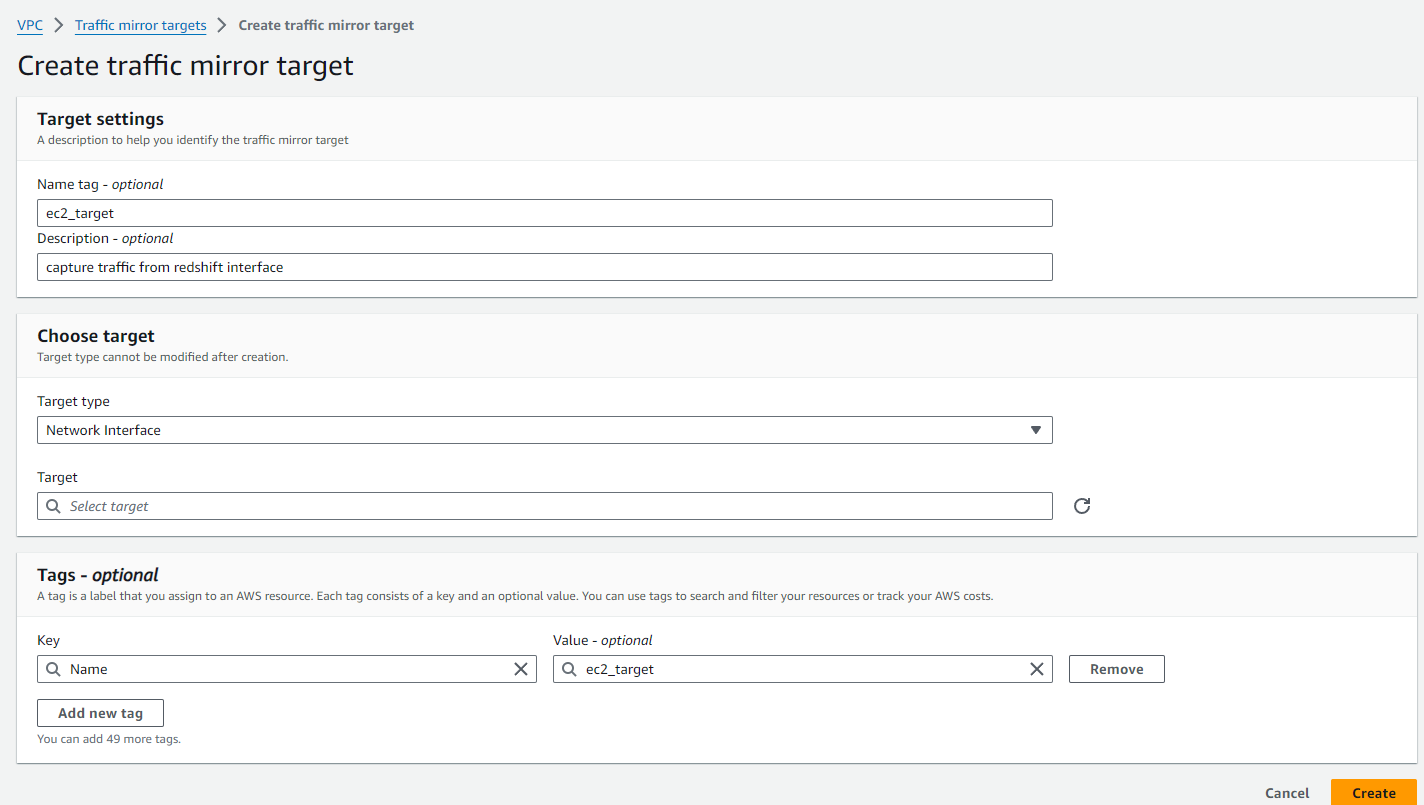

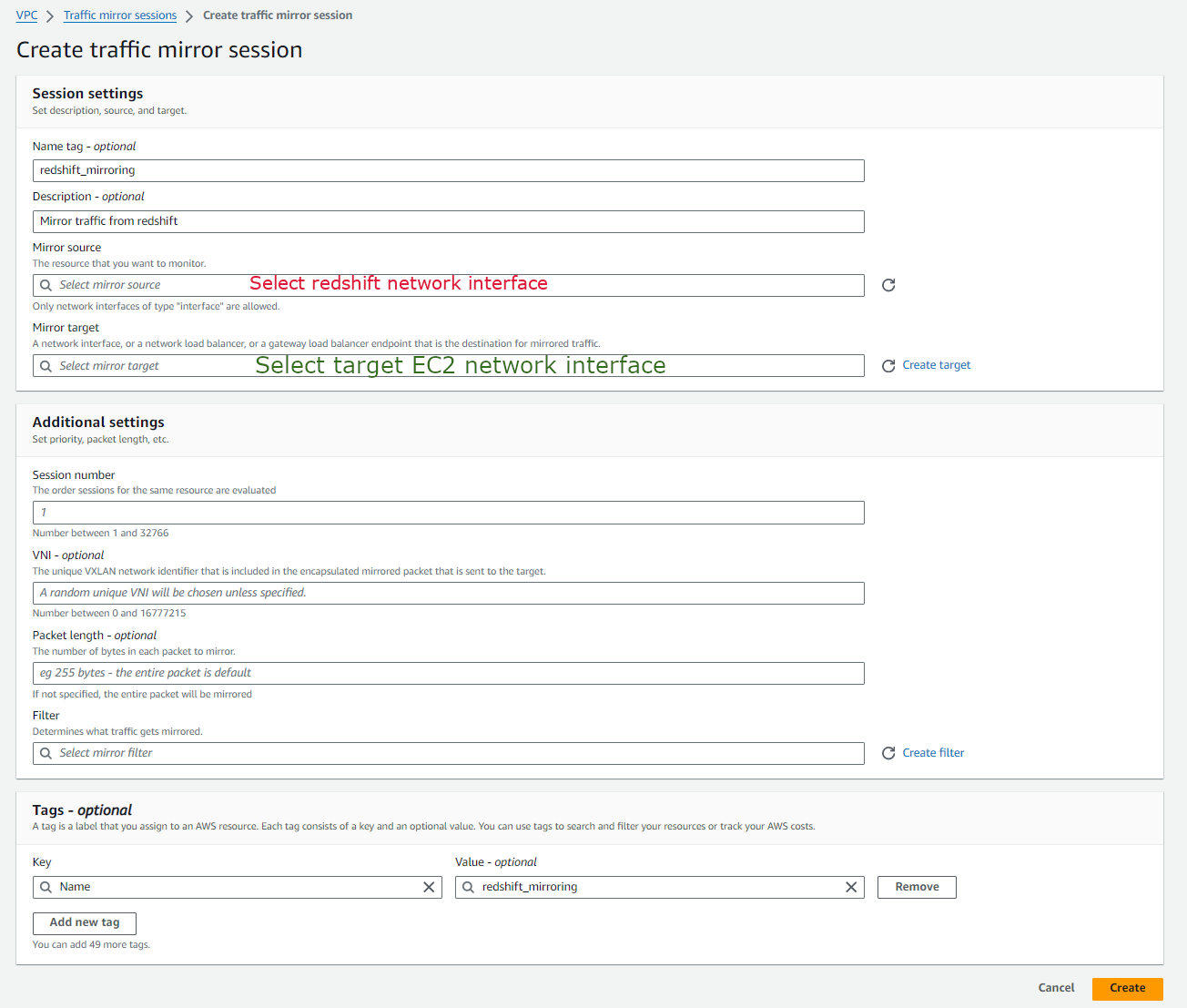

To setup AWS Traffic mirroring we first created the mirroring target to point to our EC2 instance.

The next step is to create a mirroring session that connects the source and the target.

Afterwards, the traffic destined for the Redshift cluster would be mirrored to our EC2 instance.

A look into the server side packet capture

The same tests were conducted by running the on-premise application and connecting it to the Redshift cluster. Subsequently, the packets mirrored and captured by the EC2 instance were inspected, yielding the following outcomes:

The server received the TLS handshake message ‘client hello’ from the client, and in response, the server sent the ‘server hello’ message back to the client.

That was somewhat unexpected. Initially, I suspected the issue might stem from TLS negotiations or the SSL server certificate. However, the server did attempt to respond by sending the ‘server hello’ back to the client. The current dilemma lies in the fact that the client never received this ‘server hello’ packet.

MTU and Jumbo frames, no not Dumbo the flying elephant

After conducting further investigations, I identified the root cause and promptly alerted the networking team. It transpired that the issue originated from a misconfigured network switch lacking support for Jumbo frames. It’s ironic how such a seemingly minor oversight led to significant troubleshooting efforts.

Allow me to elaborate on how I arrived at that conclusion.

Given that the packet capture from the server indicated the transmission of the ‘server hello’ message, it logically follows that the packet must have been dropped somewhere along its path to the client.

A quick traceroute command provides a visual representation of the hops along the path from the server to the client, aiding in the identification of any potential network issues or delays.

traceroute 10.78.31.19

traceroute to 10.78.31.19 (10.78.31.19), 30 hops max, 60 byte packets

1 10.141.17.42 (10.141.17.42) 10.211 ms 10.207 ms 10.203 ms

1 10.141.17.1 (10.141.17.1) 1.023 ms 1.015 ms 1.013 ms

2 10.78.31.19 (10.78.31.19) 5.789 ms 5.785 ms 5.781 ms

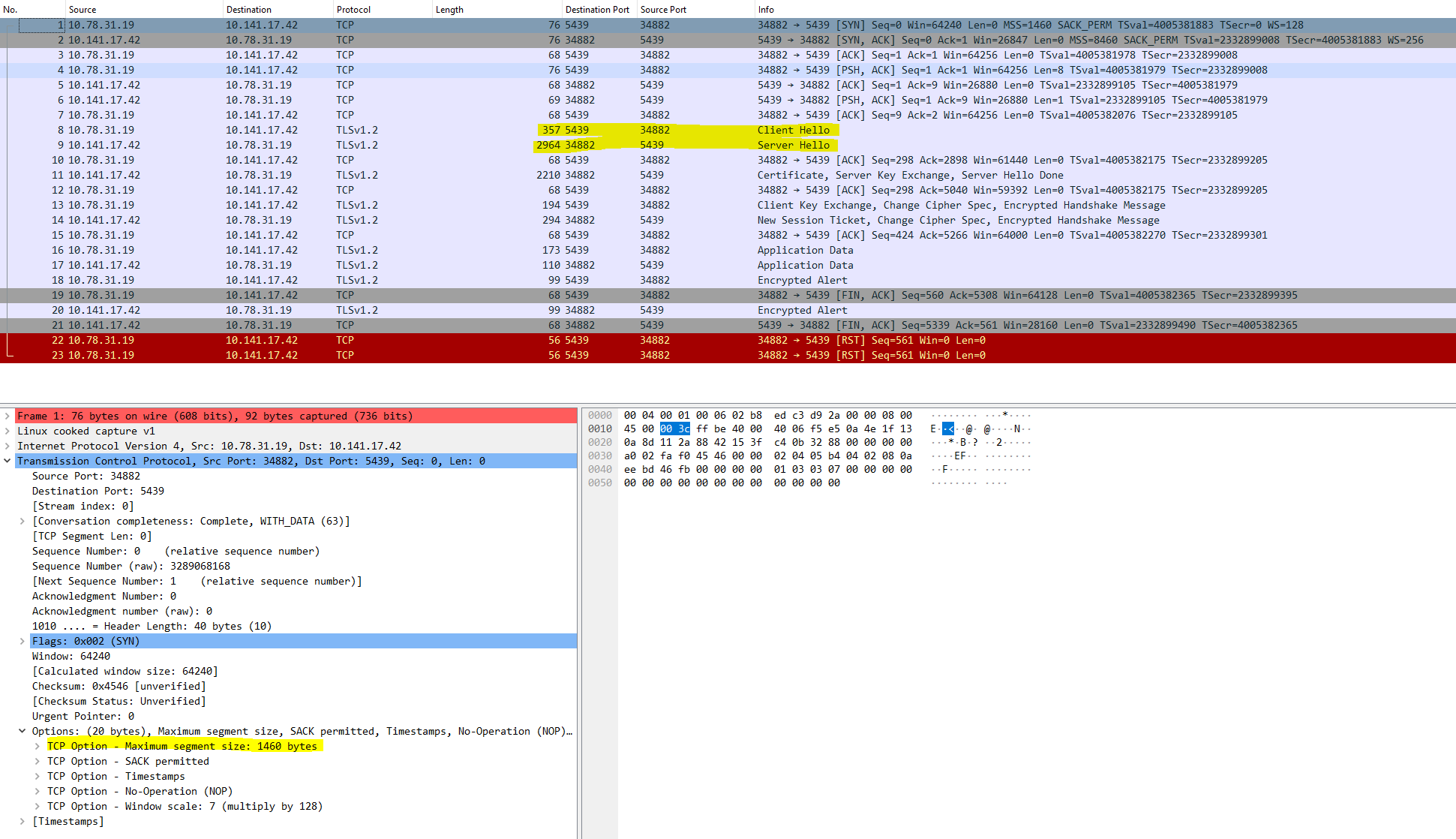

So, it’s apparent that one or more of the hops failed to deliver the packet to the client. Let’s redirect our focus to the packet capture on the server side, as illustrated in Figure 7.

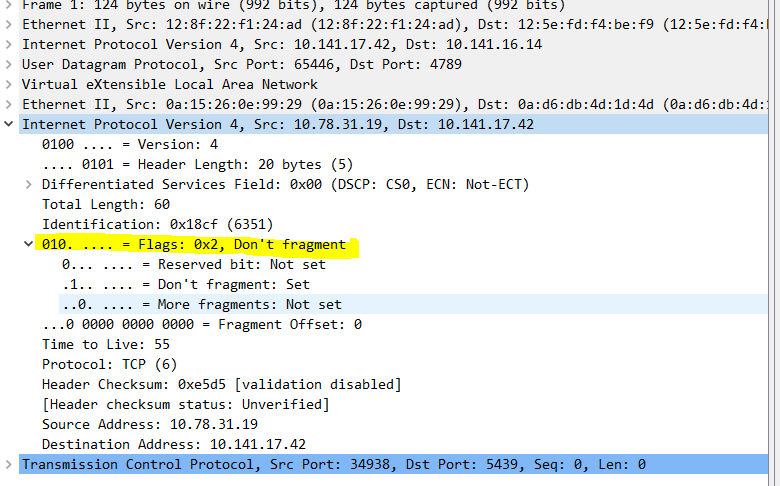

Upon closer examination, I discovered that the client’s network interface supported an MTU larger than 1500 bytes. This is evident from the MSS (Maximum Segment Size) option observed in the packet capture.

It looked like the MTU size for the client was 9000 bytes. I could also see that the client had the Don’t Fragment flag set.

So, what does all this information signify? Well, it’s crucial for comprehending the intricacies of routing network packets from source to destination, acting as the pivotal factor for pinpointing the root cause of this issue.

Let’s break it down:

- MTU (maximum transfer units) identify the maximum size of any data packet that can be sent over a network.

- MSS (Maximum Segment Size) is determined by the MTU value and signifies the maximum size of the payload section of an IP packet that can be transmitted across a network.

- Jumbo frame refers to an Ethernet frame that exceeds the standard size of 1500 bytes.

- ‘Don’t Fragment’ flag determines whether a packet is permitted to be fragmented into smaller packets if it exceeds the MTU size.

So now that the terminology is in place, what we observed was the following:

Client supported Jumbo frames of 9000 bytes meaning it had an MTU size of 9000 bytes

When client connected to server it sets the ‘Don’t Fragment’ flag indicating the packet should not be fragmented along its path to the destination. However, whether any of the hops on the path will fragment the payload depends on whether the packet exceeds the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) size supported by any intermediate devices.

The server also supports Jumbo frames and respects the ‘Don’t Fragment’ flag set by the client. It attempted to transmit as much data as possible within a single packet back to the client, which in our case amounted to 5154 bytes, surpassing the standard 1500-byte limit for non-Jumbo frames.

The fact that the client, which supported an MTU size of 9000 bytes, never received the ‘server hello’ packet suggests that the issue likely stems from one of the hops along the path. This hop may have dropped the packet because its own MTU size couldn’t accommodate the larger packet size.

Since the client had set the “Don’t Fragment” flag, the hops along the path wouldn’t fragment the packet. Instead, they would reply to the server with an ICMP message indicating “Fragmentation Needed.” This message notifies the sender that the packet is too large to be sent without fragmentation. Consequently, it becomes the sender’s responsibility to adjust the packet size accordingly and resend it.

The server did not receive any ICMP packets indicating “Fragmentation Needed.” Consequently, the packets were not resent in smaller parts by the server; instead, they were dropped.

To confirm whether one of the hops was not sending ICMP packets back to the server, we adjusted the MTU size of the client to 1500 bytes and reattempted the process. This was our observation.

And the packet capture from the server side also showed the following:

When we lowered the MTU size to 1500 bytes, we successfully completed the TLS handshake with the server, and the connection was securely established. This bolstered our confidence that one of the hops must have been misconfigured.

So, we initiated pinging all the hops in an attempt to identify which one did not support Jumbo frames and potentially failed to send ICMP packets back to the server. We employed the following command:

ping -M do -s 8000 <destination ip>

And indeed, one of the hops couldn’t handle the 8000-byte packet, which was a huge relief. This discovery allowed us to escalate the issue to the networking team for resolution.

Conclusion

Diagnosing and troubleshooting networking issues can indeed be challenging, particularly when direct access to the source is unavailable, especially in scenarios involving managed services in the cloud. Fortunately, in this instance, we were able to utilize AWS Traffic Mirroring to replicate network traffic to an EC2 instance, allowing us to conduct packet capturing and analysis effectively.

I hope you had the patience to follow along and understand how packet inspection is a really powerful tool to understand what is going on in your network and with the help of AWS Traffic Mirroring we could identify issues that would have been really hard to identify otherwise.